This answer is not going to please some people. I stand by every word, however.

For the past 30 years – at least– I have watched how we have been training children and teenagers to believe that they are perfect in every way. “Just as you are.” No one should be able to take away your self esteem because you are perfect.

Perfection is, well, perfection. It is a state of being that defies criticism. It embodies immunity. And they, those sweet, sweet children, have been granted it just by being them. No additional effort required.

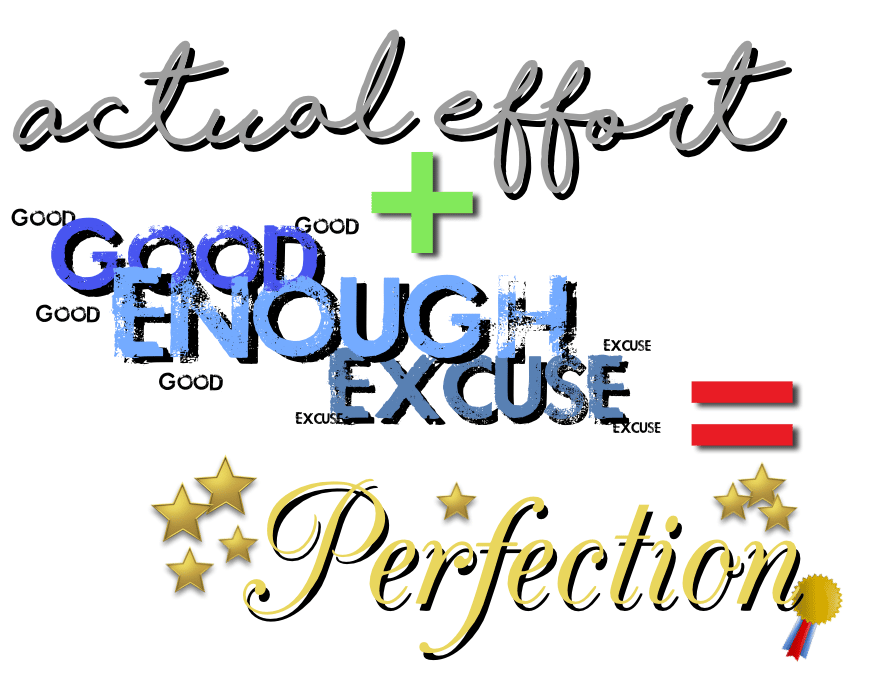

At the same time, we have also been training them that there is a very simple equation to keep that perfection:

Effort + Good Enough Excuse = Perfection

Look at any aspect of schooling and you’ll see what I mean. Look at how often students are encouraged to provide a good enough excuse in lieu of actually doing the work – and still get credit for doing nothing.

Didn’t get an “A” on your test? Well, the dog ate your homework. You drank too much last night. Donald Trump was elected President and you couldn’t cope with the trauma. You have a good enough excuse.

We’ve done this so much, and gone so far, that children have grown up thinking that they exist in a state of grace, a state of perfection that is at risk of being lost at any moment by mean people, evil people, racist, sexist, ableist people.

Personal failings are impossible; you are perfect. No one has the right to tell you that you are not, and if, for some reason, it can be shown that you are not perfect, well all you need is the good enough excuse!

Enter in the ADA – the Americans with Disabilities Act. Suddenly, anyone and everyone had the legal authority to claim a Good Enough Excuse. Suddenly, if you couldn’t do your job because you had:

- muscular dystrophy

- orthopedic, speech, and hearing impairments

- visual impairments

- heart disease

- epilepsy

- cerebral palsy

- mental retardation

- drug addiction

- HIV

- specific learning disabilities

- diabetes

… then you would have no repercussions. Not all of these were part of the original ADA bill, mind you. It was expanded because suddenly people realized what opponents of the bill warned about – if you were somehow damaged, you were immune from criticism.

And then came the sticklers. Only someof the mental impairments and conditions were considered “appropriate” excuses. Then, magically, conditions that were considered covered began to expand their definitions. Autism became a “spectrum” that included, it seems, simply being an asshole.

I have watched teenagers post long screeds of self-diagnosis about how they are Autistic or Bipolar or name-the-affliction-of-the-year in drawn out, overwrought Tumblr posts, and then explicitly call out anyone who dares criticize them because of their “condition.”

They demand immunity for their bad behavior because they have a good enough excuse.

So now, we have almost completely eradicated the need for any actual effort. The excuse has become nearly equivalent with “perfection:”

How many people see themselves now

So, in summary…

Why do people want to be seen as being damaged goods? Because they genuinely believe that they can acquire immunity for their bad behavior as a result. At one point it was an envy of those who seemed to get “special treatment” for the tolerances being made for disabilities, but then it became a get-out-of-criticism-free card, laminated, and permanently laser-engraved, to be proffered at every opportunity.

(In another screed, it’s possible to show how this very motivation leads to an incapability of handling any adversity, resulting in the genesis of the “snowflake” epithet, but I’ll leave that for another time).

Update

My good friend and colleague Omar Sultan challenged me on Twitter about this, and I’m always open to discussion on topics like these.

Omar’s point was that mental illness carries a stigma, and that people who disclose their mental illnesses typically do so with great care.

Sorry dude, think you are off point on this one. Maybe some do “brag”, but mental illness carries a stigma that no other illness of any other organ carries. Most folks I know dealing with their illness would simply be happy to be treated like everyone else.

— Omar Sultan (@omarsultan) December 20, 2018

Teens on Tumblr not withstanding, disclosure is a tough choice—perhaps you need to tell friends or co-workers to they have some context when you seem to be having a bad day, but you run the risk of being treated like a leper in the process.

— Omar Sultan (@omarsultan) December 20, 2018

Perhaps the biggest challenge for folks with mental illness is asking for help and building a support network for friends and family. Broad brush saying its perceived as asking for a handout is not helpful.

— Omar Sultan (@omarsultan) December 20, 2018

Omar has an excellent point, of course. I was narrowly focusing my answer here on the people mentioned in the original question – those who “brag” about being bipolar. So, my Venn diagram set was much smaller than those people who have mental illness. As he also pointed out, my attempt at being more brief may have the unintended consequence of making it less clear:

I know you so I get there was probably nuance to the point you were trying to make—my point is in general, the discourse around mental illness lacks subtlety. Some folks (probably too many) are going to miss your actual point and simply reinforce their existing thinking.

— Omar Sultan (@omarsultan) December 20, 2018

Obviously, I don’t write articles to confuse people, so his point strikes home.

My point here is not that people with mental illness fabricate their situation in order to be able to use it as an excuse. As someone who has more than his fair share of experience with people who have severe mental illnesses, I’m not so stupid or naive as to make such a claim.

Instead, I was referring to the point that there are actual campaigns to use mental illness as an excuse for claiming immunity for bad behavior. After I wrote this article, and as a result of Omar’s comments, I started looking for information to find out what the state of the situation actually is.

One of my claims is that the definitions of these disorders has been expanded over time. There is a lot of data to support this:

Utah Study: Expanded definition finds more disabled kids with autism (if this isn’t a “No shit, Sherlock, moment, I don’t know what is).

Psychology Today: Is the definition of Autism too Broad? While this is an argument for why it’s not, the author writes this very telling paragraph:

Ten years ago, members were mostly neuroscientists, biologists, and geneticists. That was consistent with the thinking of the day, that autism was a serious neurological disorder. Autism was certainly a pathology; the idea it might be part a human diversity was not seriously considered. Today’s INSAR is increasingly dominated by psychologists and social scientists, some of whom question the pathology model.

And there we have our first clue – the inclusion of the social scientists in the past ten years cannot escape the examination of what constitutes those social scientists’ ideological trends, something that I’ve written about elsewhere. What’s interesting about this Psychology Today article is just how it aligns with my “Good Enough Excuse” argument:

Interestingly, most biomarker research seems to classify people as autistic in line with the current, expanded, definition of the autism spectrum. That supports the idea that this broader spectrum is the more correct definition.

No, it actually doesn’t. It means that the broader definition now allows for more insurance-covered medications to be developed under the guise of helping “a crisis of increasing cases of Autism.”

And here is the final evidence to support the point, again straight from the horse’s mouth:

In that wish I join members of many other marginalized groups, for whom I wish the best for our collective success in advocacy.

There you have it. The implicit claim of immunity due to being part of a “marginalized group.”

JAMA Pediatrics confirms this as well, in a peer-reviewed study that indicates that you can Explain the Increase in the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders to changes in reporting practices. Why is this possibly a bad thing? Because when you cast a wider net, you’re bound to catch bigger (and more) fish. We’ve gotten to a point where there is a schism in the “Autistic Community” now clarifies between those “on the spectrum” and “Autism Primes,” who fit the earlier definition of Autistic people:

The media are full of stories of the “autistic” who writes plays, achieves marvels on the basketball court, or gets swindled by a used car dealer.

What do these items have in common? They have no bearing whatsoever with the experiences and suffering of those who must daily face what I can only call “autism prime.” Such people exist in a swirling, nearly impenetrable world of their own punctuated by violence, lack of articulate speech, weird obsessions, incredible indifference and a hundred other heart-breaking negatives.

What’s key here is that these definitions are often guided by legislative acts, not medical ones:

In California, the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act, passed in 1969 and amended numerous times over the subsequent 6 years, guarantees that all persons with developmental disabilities can receive age-appropriate services for specified conditions (autism, mental retardation, cerebral palsy and epilepsy).6 During that period, the paradigm for services to persons with disabilities was shifting from the medical model to the developmental model, a change implemented by state and national policies. By 1976, 21 Regional Centers were established in California to administer and coordinate those services in a community rather than institutional setting. Administrative databases from these Regional Centers are now compiled centrally by the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and have been analyzed to track trends in developmental disabilities. [Source]

Okay, but the key question here is one of Bipolar Disorder, not Autism, right? Well, yes and no. They’re both fruit from that poison tree, and both threaten those with actual issues by flooding the conversation with obfuscation from those who want to gain the same “privileges” (god, how I hate that word) as those who get special attention.

Cases in point:

Why Accusing People of Having a Victim Complex Can Be Ableist.

Beyond Awareness: Mental Illness and thee Ableism of Capitalism

Oh, and if there was one post that completely embodies the point: On “Coming Out” as Bipolar in Academia

Relief washed over her face and we went on to outline a plan on how to talk to the class about ableism and invisible disability. The following week, I implemented the plan and, while it took some time to take effect, eventually everyone in the room was more mindful (including me) about what was said and the tone used.

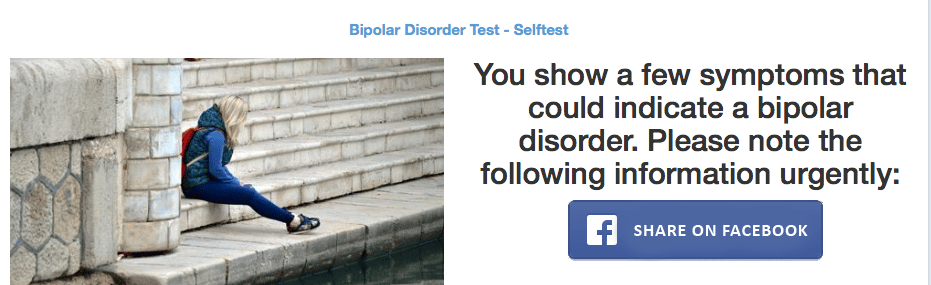

If there was ever a means of finding evidence that teens are encouraged to find themselves as bipolar, just look at the sheer number of self-diagnosis tests there are available.

Diagnosis Guide for Bipolar Disorder

What are some of the questions? For grins and giggles I decided to take this last “test”. Here are the questions along with what I put as answers.

- Did you talk more quickly or talk a lot more than usual in the last couple of weeks? [Agree]

- Did you have more disputes, fights or shouted more at people, than usual, in the last couple of weeks? [Agree]

- Did you sleep less in the last couple of weeks, but didn’t miss it and felt good? [Agree]

- Did you felt much more self-confident in the last couple of weeks? [Disagree]

- In the last couple of weeks, did you get easily distracted by things or had trouble concentrating? [Strongly Agree]

- Did you feel more active than usual in the last couple of weeks? [Strongly Disagree]

- In the last couple of weeks, did you have more interest in social interactions or did more crazy things than usual? [Disagree]

- Did you have more love lust in the last couple of weeks? [Neutral]

- In the last couple of weeks spending money got you or your family in trouble? [Neutral]

- How much of a problem did any of these cause you? [Increased Problems]

So what was the result!

Surprise, surprise…

Oh, and make sure you share your online diagnosis on Facebook! Tell your friends! Get loads of sympathy! Get the support you need from your social circle!

FFS.

Honestly, I had to stop looking, because it was starting to get ridiculous. What’s interesting is that a lot of women’s magazines seem to be more heavily represented in offering these quizzes, but I didn’t exactly do a thorough analysis. It just seems, anecdotally, that many of these quizzes appear to be geared towards girls and women for some reason.

The Quest For Immunity

So, we’re back to the thrust of my argument – that people who actively seek to be known for these conditions (and there is no shortage of places to give them confirmation), are looking for the ability to have a Good Enough Excuse to keep them in the realm of Perfection.

Well, it appears that there is something to this. In If You Criticize Me, You Don’t Love Me, Karyn Hall underscores my point about how criticism indicates a fall from grace (though her main thrust is about how such a mindset affects relationships with significant others).

I don’t have a lot of time to do a master post on this type of thing, but when you see articles like 10 Things You Should Never Say To Someone With Bipolar Disorder, it’s easy to see why anyone who wants to avoid such criticism would claim to have it – just to avoid the criticism.

Bottom Line

As I mentioned, I’ve had a lot of experience for many, many decades with people who have severe mental illnesses, including (but not limited to) Asperger’s, Autism, and Bipolar Disorders. I know how serious it is (and can be), and the hell that everyone around them goes through. I find it absolutely puzzling why anyone would want to be put into that category – I really do.

For people like Omar, who has personal experience with this as well, I do understand the need to be careful about stigmatizing people with legitimate problems. Ironically, that’s precisely why I am so harsh – it’s the posers who wish to be sympathized with, the adopted “struggle” they wish to claim, that I have no patience with. I think Omar would actually agree with me on that part.

So I return to the point of my article in the first place: Among those people who fall into this category, this is why I think they do it. This is the evidence that I have seen over the past few decades, since the definitions of these disorders were so greatly expanded – and protected by legislation – since the mid-1990s.

I hope that clarifies a bit (and so much for my attempts at brevity!)

Comments

Point taken. But, there is another part about revealing if you are bipolar — and that is to take the stigma off mental illness. Using it purely as an excuse is wrong. But there is also nothing wrong about having mental illness, though there still is a lot of stigma about it. There used to be a stigma about having cancer years ago.

BTW, the intention of the ADA was to focus on what people could do at work, rather than focus on what they couldn’t do. The positive results of the ADA is that people with physical, cognitive and psychological challenges could become effective members of the workforce rather than be cast aside. Of course, the law of unintended consequences has reared its ugly head and there are those folks who cast themselves as victims. In my experience, that is not a majority of people, but enough to spoil it for everyone.

I’ve updated the article, and would like to hear your thoughts as a result.

The update clarifies, though there’s one paragraph I want to follow up on:

“As I mentioned, I’ve had a lot of experience for many, many decades with people who have severe mental illnesses, including (but not limited to) Asperger’s, Autism, and Bipolar Disorders. I know how serious it is (and can be), and the hell that everyone around them goes through. I find it absolutely puzzling why anyone would want to be put into that category – I really do.”

I was diagnosed with clinical depression 24 years ago. I am sure I suffered from it longer than that. It wasn’t exactly surprising given my mother was bipolar. Medication, talk therapy and learning coping skills keeps the “Black dog” (as Churchill phrased it) pretty much at bay. It’s not a secret, but it’s not something I broadcast. I usually save revealing my condition when there are people who clearly need support and feel as if they are the only ones who feel that way.

I will admit that I have been a bit more open about it since I got tenure.

I would love NOT to be put in that category. When the Black dog visits, it is no fun. On the other hand, people with truly diagnosed mental illnesses are still treated with stigma, and, so, the more we can talk about it, the better.

I think the “truly diagnosed” part is key. That means being diagnosed by medical professionals, not from checklists from the Internet, and not by people such as parents, teachers, or friends.

People who just declare themselves as having invisible challenges are seeking attention, looking for an excuse, or both. They also do serious damage to those who really do suffer from such conditions.

“On the other hand, people with truly diagnosed mental illnesses are still treated with stigma, and, so, the more we can talk about it, the better.”

Of this I – and I think Omar, though I won’t speak for him – agree. It seems to me, though, that there is a *major* difference between telling someone *that* we must talk about it and *how* we must talk about it. The people we are referring to here, the virtue signalers, the pity-me people, the attention-seekers, always seem to want to drive the “how” part of the conversation. They (again, I’m talking about this specific set of people) always want to claim some sort of untouchable position.

To that end, then, it appears that you and I do agree, ultimately. Thank you for returning to the article and adding your additional insight.

It’s a luxury to be able to brag about being bipolar, instead of having schizophrenia. There is all this media of bipolar being associated with creative genius, while the opposite with schizophrenia. There is so much stigma with schizophrenia, that they pretty much have to fake normal as much as possible, while people diagnosed with bipolar don’t have to hide it so much.