Recently I came across a review of the movie Whiplash by Adam Neely, a YouTuber who wanted to talk about it from a jazz musician’s perspective.

The entire reaction is definitely worth watching, because Adam goes through some of the culture of Jazz musicians that the movie definitely misses. But it was this part that really struck a nerve with me:

Why did this resonate with me? Because it never even dawned on me while watching the movie. The absence of joy in the movie – joy about the music, joy about the camaraderie, joy about the performance, joy about the resonance created when top-notch musicians are in sync with each other – was completely in the realm of my own experience.

Growing up, playing music was something that I took for granted. I was good – very good, in fact – gaining all-State chairs, invited to the McDonald’s All-American High School Band for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade, All-American European High School Band tours, and even had an audition lined up at Julliard (that sadly I was talked out of, and so never went).

All along the way, though, I was actively discouraged by nearly everyone except a very few number of people – people who, unfortunately, were either in no position to help or had to compete with people who had far greater sway over my day-to-day musical journey.

Today, December 2, is the 47th anniversary of my very first piano lesson. Surprisingly, I remember it very well. It’s not one of my earliest memories, but it is certainly one of the clearest from that age. I remember starting off enthusiastically, but quickly learned that I was not ‘allowed’ to experiment. At the age of 6, my father grew irate at me for moving ahead in my primer book and playing pieces that I hadn’t been specifically instructed to practice.

It set a tone that lasted a lifetime. Practicing was work, dammit. How dare you try to do something that you enjoyed?

I took lessons until I was 13, when we moved to Guam (my father was in the Navy). I still played, but not when he was in the house. Moving back to the States at 15, we found another teacher to get me back on track. Unfortunately, that teacher was far more interested in ‘correcting’ my body posture and hand positions and pressing up against me in uncomfortable ways than teaching me how to improve my piano playing. He didn’t start off that way, and at first I wasn’t sure what I thought he was doing was what he was actually doing. Then it became clear. I quit after four "lessons."

I never took another piano lesson in my life.

Instead, I played in the high school orchestra and marching band. I played melodic percussion – xylophone, glockenspiel, tympani, chimes, timbales, and so on. My junior year, we got a new band instructor – Mrs. Marinaccio, a new graduate from the University of Rhode Island who had never had her own high school faculty position before. I think she was probably about 24 years old at the time, but to me at 16 she looked to be much older.

I’ll never forget how she introduced herself. “This is my band,” she said without a hint of humor. “You will do what I say.”

You can probably already imagine how well that went over.

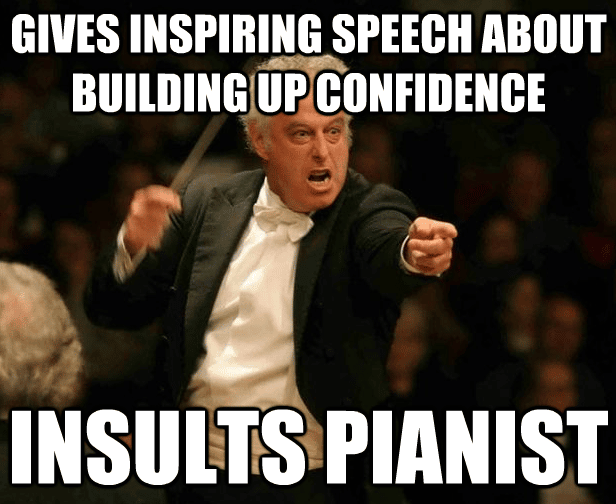

She ran the band and the orchestra as if we were handling toxic waste. Just like Fletcher in Whiplash, she would yell, scream, and belittle students for the slightest misplayed note. Now, Fletcher was in a completely separate class (and one that I would experience in one of the All State conductors), but she was far more interested in attempting to control her class than play actual music.

She and I clashed almost immediately. At the time, I could play complex music by ear (I cannot do this any longer). This drove her absolutely nuts, for some reason. One day during jazz rehearsal, I had forgotten my music (I was playing piano in the jazz band). She was livid, because the song required a strong piano foundation, and we had only played it once, about a month before.

She went off the deep end, accusing me of wasting her time and everyone else’s. Personally, I think she was particularly harsh because she had a friend visiting from her university days as a guest. Whether she was concerned about losing face or trying to impress her friend, I have no idea. All I know was that this particular time she was even more OTT.

“Look,” I said, losing my own patience (I had a quick temper back then). “Just hum it for me.”

“What?!” she asked.

“Just hum it for me,” I repeated. “I just need to know how the song goes.”

It was obvious that she didn’t want to do it. It was beneath her. One of the other students, though, obliged.

“Got it,” I said, and I played it.

That made her fly into a rage no one had ever seen before. “I thought you said you didn’t have the music!” she cried. She was convinced that I had been trolling her, that I had the music and was trying to make her look bad in front of her friend.

“I don’t,” I said, calmly.

Mrs. Marinaccio looked to her friend, who shrugged. “He doesn’t,” she confirmed. Mrs. Marinaccio looked shocked, her mouth agape, stunned. She stomped off her podium and charged me at the piano, fully expecting to see secret sheet music. Of course, there was none.

“Don’t you just hate people like that?” her friend said, trying to lighten the mood.

Well, Mrs. Marinaccio certainly did. After that day, she took every possible opportunity to make my life entirely miserable, mostly by not allowing me to play. I would spend weeks in class (classes were daily) without playing a single note.

Things weren’t much better at the All-State level. Nor was it on the European Tour, which I went on immediately after graduation. Now, lest it appear that I am attempting to play myself out to be the hero against tyrannical conductors, let me put that idea to rest. I was, unfortunately, too much of a coward to intervene when I saw blatant bullying of student musicians.

After the European tour, I put down my sticks and never picked them up again. It’s a shame, too, because I loved my Vic Firth sticks…

It took Adam’s video to remind me, though, that it wasn’t always a matter of draconian conductors and teachers. If all that’s what there was, I don’t know why I would have continued to play at all. The reality was that I loved playing music. I loved it when I had to play 5 instruments in one song, racing from station to station, often holding two different pairs of sticks in my hands at the same time to be able to make the timing.

There is humor in music, too. Hang around tromboners for a while for example, and I dare you to try not to smile. Humor – especially improv – requires more than one person, and for those people to work off each other. Music makes it easy to do, and the bond that is created by a group of people playing (yes, pun intended) is something that is indescribable to someone who’s never experienced it.

The next and last time I played music in public again, I was in grad school. I played in a cover band, playing keyboards. When our bassist quit, I picked up the bass and played my first gig 2 weeks later. It was the last time that I showed the natural talent of music without too much effort.

We played originals, too, some of which I wrote. For three years our band, Infomania, played around Athens, Georgia, on the same stages that R.E.M., Matthew Sweet, and the B52s played (not at the same time as those bands, of course!).

Over the last 20 years, though, I haven’t played much. I picked up the bass again about 5 years ago, and tried to get back into the groove of enjoying playing. But things don’t come as easily as they once did (not even close). I don’t feel the creativity or the desire to play or experiment or goof around with the instrument.

I’d lost the joy.

Whenever I think about sitting down at the piano or picking up the bass, I know that I need to do fingering exercises and scales. You can’t play fast unless you know how to play fast, which comes from getting the muscle memory into your fingers.

Sadly for me, my fingers don’t work they did before I turned 18. I mean that literally, as I had a severe hand injury when I was 18 that tore through three tendons on my left palm and required major reconstructive surgery. The fact that I can play bass at all, much less piano, is testament to an incredible surgeon and nearly a year of very painful physical therapy. Over time, arthritis did the rest.

So, I will never be able to shred. Not again, anyway.

In a way, had something like that happened if I were at a school like Julliard it would have been utterly devastating. By that time, though, I had already given up on music as a career anyway.

Over time, though, it’s interesting that what has stayed with me was not the joy of playing music (which was intense), but rather the more unpleasant aspects of playing music that had nothing to do with music at all. What’s been left is what is shown in Whiplash, a confrontational and adversarial relationship between the musician, his peers, and his ‘mentors.’

I guess the only thing to do - now that I’ve realized what I hadn’t realized about losing the joy - is to work on simply enjoying playing again. It may seem like a no-brainer, but when you don’t even understand that it’s been taken from you in the first place (until someone like Adam points it out to you), it’s not exactly intuitive.

It’ll take some doing (or undoing), because every time I’ve picked up an instrument for the past 5 or 6 years, it’s been to work. Practice. Scales. With ghosts shouting in my ear. It’ll take some time to ignore those ghosts, for sure.

I don’t know. Maybe it’s just me. I didn’t have the strength of character to really stand up for the joy of music before I was 18, even though I had the talent. After the injury, I simply didn’t really see the point. I have to give Adam Neely a special thank you for helping me realize that there was something worthwhile at some point, and perhaps there can still be.