Why Flowers for Algernon?

When I was in growing up, I was obsessed with fairness.

“That’s not fair!” was a constant mantra for me.

“Life’s not fair,” my mother would parrot back to me – her own mantra. It was a dance of Sisyphean proportions.

She was right, of course, because life isn’t fair. Sometimes the wicked go unpunished, and the good deeds of good people go unnoticed. For me, growing up in the 70s and 80s, I felt this unfairness deep into my soul.

As a dependent of a military doctor, we moved every two years or so. In eighteen years, twelve different schools. Sometimes I would be placed in remedial classes, being so far behind that I needed “special” help to catch up. In others, I would be in the “gifted” programs because I could read and write far beyond my classmates… and get beat up for the privilege.

On top of it all, I had dyscalculia and didn’t even know it. I thought of it as “numerical dyslexia,” where the numbers jumped around and would shift positions constantly. My father – the Ph.D. from MIT – simply couldn’t understand how and why I couldn’t get very simple math programs right. He thought I was an idiot. I thought I was an idiot – all the way up through college and into my graduate school career.

Everyone seemed smarter than me. There were no standards, no measurement by which I (or my parents, or my classmates, or my teachers) could say, objectively, that this is where J shines or that is where J needs improvement.

I read Flowers for Algernon the same time that I read Animal Farm and The Human Comedy, books on my parents’ proscribed summer reading lists. I was seven years old.

Today, I couldn’t tell you what The Human Comedy was about, other than it took place in WWII (yes, I know, I could look it up, but I’m making a point here). Animal Farm and Flowers for Algernon, though, struck me to the core.

Now, more than 40 years later, I’m still stunned by how I react to the unfairness illustrated – no, promoted – in those two books.

For years after reading Flowers for Algernon, I didn’t even know I identified with Charlie Gordon as much as I did. How he worked his way through the world resonated more profoundly than I ever realized – that is, I didn’t realize it until I picked up the book about a week ago.

Synopsis and Spoiler-Free Review

Flowers for Algernon is a Hugo- and Nebulon-winning science fiction story from Daniel Keyes, first published in 1959. It was made into the movie Charly in 1968, starring Cliff Robertson and Claire Bloom, with the former winning a Best Actor Oscar for his performance. It's written and set in a time of scientific and moral exploration, where technological and ethical boundaries are stretched and warped.

Charlie Gordon is retarded man (more on this word later) in his early thirties. He is what is called a “high-moron,” someone whose IQ is somewhere between 60-70. Abandoned by his family, he works at a bakery in a job that his late Uncle set up for him.

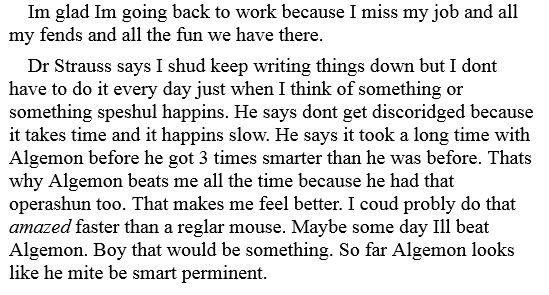

Charlie desperately wants to be smart. We know this because the book is written in diary form, and the reader can watch his development through Charlie’s own writings. Charlie has been chosen for a new experiment – a surgery to be performed on his brain that will help him grow, intellectually.

Accompanying him on his journey is Professor Nemur, the scientist who developed the technique; Dr. Strauss, the psychiatrist who performed the operation; and Alice Kinnian, the teacher who taught Charlie working as a teacher for mentally challenged adults.

And, of course, Algernon.

Algernon is the major success story for Nemur and Strauss, a laboratory field mouse who was the first (and only) to show stratospheric leaps in intelligence. It is Algernon’s success that emboldens the scientists to attempt the procedure on a human subject.

The results from the experiment happen quickly, but not fast enough for Charlie. He wants to make up for lost time as he becomes more aware of the world and his place in it. He begins to realize that people he once thought were his friends, were anything but. There is a difference, after all, between laughing with you and laughing at you. Charlie begins to learn that difference, and begins to hold a value to that lesson and, ultimately, to himself as a person.

As he grows in self-awareness, he struggles to be seen as a human being, as someone other than “an experiment.” The only comfort he can take is that there is one other being who has gone what he has gone through – Algernon.

Charlie’s transition from retarded adult to legitimate genius is a painful one for him – a pain that he did not expect and for which he is woefully unprepared. He struggles with his self-awareness, is tormented in his dreams of his family – the cruelness and unfairness of how he was treated as sub-human. Each memory and recollection of his childhood brings with it untold depths of trauma.

He suspects that he is not yet smart enough to be able to process the emotions, and wishes that he could get more intelligent, and faster. He reads up on everything he can get his hands on: science, literature, biology, physics, psychology, music.

Human relationships continue to elude him, however. His connection to Alice Kinnian becomes complicated. They form an attraction and a bond, but his constant changes form an emotional and intellectual barrier as he quickly outpaces her ability to keep up with his learning and knowledge. Moreover, any attempt to move beyond a platonic relationship winds up in disaster as the “other” Charlie – the emotional persona still locked in a retarded growth state in his mind – panics at every attempt to grow closer.

All the while, Charlie is haunted by his own past – one that he struggles to process, compartmentalize, and eliminate. He gets frustrated and angry because his relationship with the scientists become more and more strained. They see him as little more than an experiment, a genius they “made,” and during one particular moment of intense anger at yet another public humiliation (as he sees it), he has a flash of insight.

They have made a mistake. A terrible, horrible mistake. One that could cost him his life. How much time does he have? Can he be the one to solve the problem?

Now For The Spoilers

Feel free to skip this section and jump to the next one if you’ve not read the book (and I truly hope that you do).

By the time Charlie has realized the danger he is in, Algernon has already been behaving erratically. Algernon’s behavior becomes more and more aggressive, unpredictable, and even violent. He’s not motivated by the pursuit of the challenge any longer, or even food. The little mouse, once docile, energetic, and friendly – is now morose and apathetic.

Charlie attempts to understand the changes in Algernon while at the same time is coping with his own demons. He is beginning to rebel against the scientists, especially as his intellectual capacity far surpasses their own. He becomes more and more disillusioned with the men and women he had admired just weeks before, considering them frauds and posers. He becomes convinced that he could improve upon Nemur’s theories, if only he were seen as something more than just an object of scientific curiosity.

His breakthrough revelation comes as Charlie and Algernon are at a scientific conference, where Prof. Nemur is boasting (to Charlie’s ears) about having created Algernon and Charlie thanks to his theories on intelligence. He struggles with the desire to stand up and contradict the scientists. Instead, he opts to cause a little chaos. He lets Algernon escape into the crowd.

Charlie and Algernon go into hiding, where he concocts a plan to negotiate with the Institute for his own research plans without Nemur and Strauss. Getting approval, he goes about trying to figure out a way to save himself and Algernon.

As we read Charlie’s description of Algernon’s troubles, we soon see that the animal is neurologically unwell. Worse, we know that Charlie will soon face the same fate. He’s racing against time, but there comes a point in time when he finally acknowledges that there will be no way to undo the deterioration of either of their minds.

Charlie is frightened for the first time. His younger self still haunts him, torments him. The genius Charlie has never completely left the former version of himself behind, and he is frightened. He begins to forget things, lose his faculties. He has reunited with Alice, who has come to stay with him and provide him aid and comfort. He is losing control, however, and thinks she pities him, mocks him. His frustration causes him to lose his temper often.

Through Charlie’s actions we indirectly discover the torment that Algernon went through. In his own way, Algernon had it worse. Unlike Charlie, he could not express his frustration at forgetting things that he knew that he should remember. Running mazes perfectly twice, and then getting lost on the third try, Algernon’s frustration causes him to go berserk. He runs into the wall repeatedly, violently. Then he curls up in the corner and becomes catatonic.

The episode encapsulates Charlie’s own descent. But Algernon cannot communicate as well as Charlie, unable to express himself and thus leaves Charlie (and the scientists) with a mystery to solve. It’s only because we experience Charlie’s deterioration through his writings, do we come to understand what Algernon was going through but unable to share.

Algernon’s fate was to be the same as all experimental field mice – a date with the incinerator. Charlie refuses to let that happen, though, and gets permission to take Algernon with him for a proper burial. By this point, Charlie is already aware that he is no longer the genius that he had been, and yet is still aware enough to understand that the Home for Retarded Adults awaits him – his own version of the incinerator. He does not want to go to the home where the boys with “silent minds” reside.

It’s a descent as quickly as his meteoric rise. In mere weeks he is reduced to where he began, struggling to understand the events going on around him, and the motivations of people who wish to torment him.

At the same time, he regains an awkward sense of peace that he did not have while he held onto his intelligence. His anger has left him, and he has his friends who have taken him back into their fold. He has re-found the sweetness of character that made him a viable candidate in the first place.

His relationship with Alice is obliterated, though. He cannot read his past entries any longer – the words are difficult to understand. He has forgotten that they had been close, lovers. One day he innocently returns to her classroom, eagerly awaiting the "usual" lesson. Alice, unable to cope with his presence (and wide-eyed innocence) breaks down and must leave. Charlie, suddenly realizing that he should not be there, abandons the classroom before she can return.

He knows that he should not ever return to the classroom, even if he doesn’t understand why. Even so, he doesn’t want to hurt her.

Charlie’s final entry leaves open the possibility that his decline will stall, but it is unlikely. As a reader, we want to believe that he has simply returned to his original mental state and that he will be spared Algernon's fate.

We know the truth of it, however. We have seen what awaits him. Charlie visited the Warren State Home while he still had his faculties, not allowing the staff to know why he was taking such an interest. Charlie spends considerable amount of time in his writings afterwards discussing how he fears going to the home. He understands its nearly inevitable, and he even considers suicide in order to avoid such a fate.

Ultimately, however, he decides that it’s best that he go to the Warren State Home for everyone’s benefit. He creates a postscript that whoever reads his entry will remember to leave flowers for Algernon.

The Power of Flowers for Algernon

Flowers for Algernon illuminates Charlie’s world without being preachy. Unlike modern novels that are heavy-handed with the virtue-signaling, the book immediately wraps the reader in a cloak of empathy. It’s refreshing to be able to become absorbed in a character without being brow-beaten in the process, or worse.

Indeed, when struggling to adapt in constantly new environments (and feeling like I was failing more often than not), I could see a reflection of myself in Charlie. It felt as if no matter what I tried to do, I couldn't stay ahead of the game. I shared his disillusion and frustration with the lack of fairness.

Between the time that I read the book at 7 and returned to it some 45 years later, I had distilled the story down to the parts that meant the most to me. From time to time, the emotional power of a scene or an interaction between the characters would come back to me as I relived homologous moments in my own life.

I had mis-remembered some things, though. For example, I could have sworn there was a passage that had been written entirely in German, or perhaps some mathematical equations written into the entries. The edition that I read had neither of those (it was re-printed in 1994). Or, they may not have existed at all. I remembered absolutely nothing about the sexual elements in the book, for instance; I completely forgot everything about them. Of course, at 7 years old, it’s not the kind of thing that was present in my mind, either.

Like Charlie, I was constantly a fish out of water, unable to understand the strange customs and languages of the places that I lived. (“Malaga mumu, laña?”) Nearly every year was a new school, a new home, a new set of standards to meet… or fail to meet. All Charlie wanted was to fit in, and was convinced that the reason why he didn’t was because he wasn’t smart enough. I could certainly relate.

Charlie’s existence haunted me over the years. Nothing about his life was fair. It wasn’t fair that he had the heart and soul of a champion, but the mental incapacity to connect with people. It wasn’t fair that he could gain intelligence and still be seen as a mere object, rather than a human being. It wasn’t fair that just when it looked like he might be able to achieve greatness, make up for all the wrongs done to him, that he would lose it all again.

I internalized Charlie Gordon over the years. Not continuously, of course, but certainly parts of him emerged every time I moved to a new school, or state, or country. I hadn’t even realized that was the case until I re-read the book and could instantly pick out specific moments in my life with laser-sharp focus where I had felt exactly the same way as Charlie.

And none of those moments were flattering.

Like Charlie, I responded at first with bewilderment. Then with an insatiable desire to get people to like me. Then with a deep, profound anger.

Charlie’s story is one that brings to light the curse of mental retardation – I use that word on purpose, because it is about being slow, not disabled – and the lack of patience from the world around him as he tries to adapt the best he could. In the end, no matter whether he was slow or a genius, he would never fit in. He had to assert his own will on an unfair world.

A Word About The Word

Flowers for Algernon has the dubious “honor” of being banned for “explicit sex scenes and offensive words.”

The book does contain both elements, in a way. I disagree that the sexual content is explicit, however, as there are no descriptions of sexual acts (the closest we get is a reference to Charlie “making love” to Alice, and some off-hand referrals to Charlie’s sexual responses to women (both growing up and as an adult).

The use of the term “retarded” in the book (I said I’d return to this) may strike modern readers as odd or insensitive, but the term is never meant as an epithet – either directly or accidentally. In fact, the term retarded was designed to replace the previous terminologies that had become insulting.

The use or misuse of the term is best left for another time and place, and Rick Hodges wrote a phenomenal essay on the issue in 2015. It’s definitely worth a read. Much better than I could do, in fact.

For now, though, let us suffice to say that the term is used in Flowers for Algernon in the appropriate medical usage of the time frame, with absolutely no reference to slighting or insulting any group of people.

Bottom Line

At Late to the Party reviews, I usually try to pick up on media content that people might have missed, or overlooked.

In this case, though, I write about Flowers for Algernon because the book is simply impactful. It's a great book. It gets you to think, gets you to feel. It pulls you out of yourself and puts you back in, different. Better. More thoughtful.

It's profound in its simplicity of structure, it’s complexity of emotion, and its empathy for not just the main character but of those around him. It's worth revisiting or, if you've never experienced it, taking the experience for yourself.

It’s a book that makes you think and feel. It’s one that forces you to examine your own perspective on life, and makes you come to grip with the unfairness of forces out of our control. It’s not the cautionary tale of, say, a Michael Crichton book, or the morality tale of Frankenstein, but rather a “walk a mile in your moccasins” approach to enlightenment.

Charlie represents our own struggles in trying to piece together the threads that turn us from empty shells of knowledge into fully-formed human beings.

Many classic books are one that you have “want to have read,” but gain no pleasure in actually reading them. For many, Atlas Shrugged, Animal Farm, and/or 1984 may fall into this category – seminal pieces of literature that can be difficult to slog through at times.

Flowers for Algernon is not like that at all. It’s a true page-turner; you constantly find yourself wanting to know what happens next. Charlie is a mystery; he may have gained super-intelligence but was hunting for the emotional gaps in his life experience. You want to see if he can figure these important pieces out. I read the last 100 pages in a mad rush because I simply couldn’t put the book down.

This brings me to one thing of note about the book. It’s possible to consume it in audiobook form, but I highly, highly recommend avoid that. Much of what we learn through Charlie’s growth and experiences are reflected in his command (or lack thereof) of the written word. His choices of spelling play an important role in understanding his character and development. It’s certainly a book worth reading with your eyes, rather than your ears.

If you’ve never read the book, you have cheated yourself out of a truly powerful experience. And that would be, ultimately, unfair to you.