Simon Sinek gave a talk, published in a clever (and humorous) video on YouTube that discusses the nature of the “Millenial Weakness,” including the perfect storm of influences that have led to general unhappiness in an entire generation of people born from around the year 1984 or so.

It’s a 12-minute video that is well-worth the time. Unfortunately, his points are derailed in the last 2 minutes but the bulk of his analysis is quite valid and, as I said, amusing to watch.

Who Is Simon Sinek?

Simon Sinek, from Wikipedia

I confess, I didn’t know who Simon Sinek was. I figured that since he wasn’t actually introduced in the video, he must be someone that I should have known about, but didn’t (this is fine – I didn’t need to know about who he was before I heard what he had to say). So, I looked him up on Wikipedia and, given his performance on the video above, learned that he is a book author and motivational speaker.

Breaking Down Sinek’s “Milennial Weakness”

Mr. Sinek’s analysis of the reasons why Milennials are, ultimately, unhappy – especially when it comes to satisfaction in the workforce – is extremely good. Many of the things he has brought up have been published here on this blog by myself and others.

- Ineffectual parenting

- Participation Ribbons

- Overdeveloped sense of entitlement

- You Can Have Anything You Want

- Immediate Gratification

- Addiction to micro-validation

In a nutshell, Sinek asserts that an entire generation has grown up with low expectations – from others and of themselves – and have no way of getting “from here to there.” That is, all of these have robbed Millennials of the knowledge of how to achieve anything, because the ability to achieve has been denied them.

The irony here is that the rules and motivations to prevent a generation from feeling like a failure has turned an entire generation into one who feels like they have failed.

To Sinek, then, this leads to a fundamental breakdown of effective communication, as they place the onus and responsibility of others – their parents, peers, or their job (or, I might add, the government) – to provide esteem and satisfaction. To compensate, they turn to technology that provides micro-boosts of validation that they get from “likes” or new “friends,” a constant stimulus-response that is highly addictive.

This addiction to immediate gratification has robbed Millennials of another important lesson for life – the ability to calibrate what it means to earn something. This includes, but is not limited to:

- Skill sets

- Deep meaningful relationships

- Stress coping mechanisms

- Patience

Worse, it means that what is or is not acceptable behavior gets muddied. There is no “scaffolding” process in relationships, where young men and women need to go through awkward moments in order to eventually get the dating and courtship ritual right.

This inability to “go slow” means that Millennials have no idea how to find meaning or significance – that is, they don’t have an idea how to make an “impact.” Given the fact that everything has either been handed to them, forcibly equalized, or bundled for immediate consumption, if they don’t accomplish some vague notion of “impact” or “importance,” they want to quit.

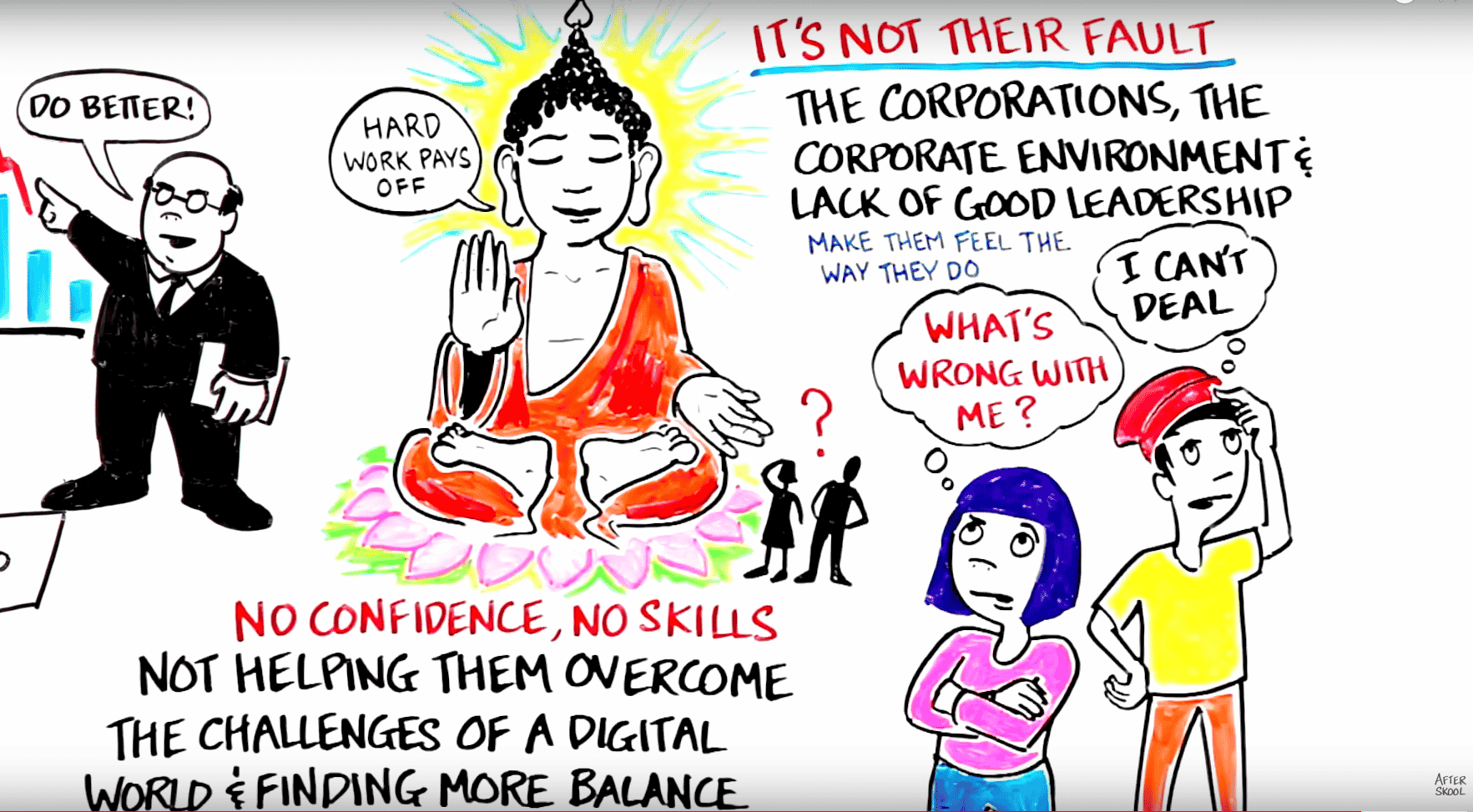

Sinek concludes with a call to corporations and businesses to pick up the slack. He chastises corporations for not providing Millennials the confidence and skills to “overcome the challenges of a digital world and finding more balance.” He believes that it is the corporation’s fault, not Millennials: “the corporations, the corporate environment, and the lack of good leadership make them feel the way they do.”

What Sinek Gets Right

Now, for a 12-minute speech, Sinek nails a lot of the problem down in clear, easy-to-understand language. There is a lot to be impressed with, if only for his ability to concisely pack in a lot of information into a short period of time.

Part of what makes Sinek’s talk so intriguing is his inclusion of addiction to the mix. What’s important here is not that social media technology is addicting, it’s how it augments the other causes and effects. The addiction of being validated for being is more important than the validation for doing, and the cycle begins afresh every time someone checks their “likes” notifications.

Where this becomes especially problematic is when this intersects with the real world. At a recent so-called technical conference that I attended, for instance, there was very little actual technology going on. Social Media references to the conference were more about the superficial interactions between people, virtue signaling, and threats of social disenfranchisement should the script not be followed.

In other words, the very purpose of the conference – to further the work technical ability goals of the attendees – took at best a second- or third-place to the instant gratification monster.

What Sinek Misses

Sinek is, of course, correct in all of his assertions about the nature of the causes and effects of what identifies general Millennial malaise. What he misses, however, is that the same kind of criticisms have been applied to Gen-X and Baby Boomers before them as well.

This is actually more important than it might appear at first. There is a general belief that the rules have changed for Millenials, and changed unfairly.

Even here on this website, Diogenese wrote:

What I see is a generation or two that climbed a ladder that always worked. They broke that ladder by putting too much weight on it, but they made it to the top for the most part. My generation is free-soloing the cliff face, listening to those at the top yell at us for going to slowly or slipping and falling. That would make any rational person start to get angry.

I love Diogenes’ perspective, because what it means is that somehow, somewhere along the line, an impression was given that no one older than 35 ever had to work to accomplish anything, that – like the Millennials, everything was given to them. I love the perspective because it illuminates the gap in perception of experiences, and provides a clue as to where some understanding and common ground can eventually be found.

The metaphor is a good one, I think, but if you look back through the course of history you will see one constant theme – the ladder was never as sound as people thought that it was, because it was never as sound as people thought it should have been. Much of the advances (in the United States, anyway) in technology and industry came because people had to build their own ladders. We call those ladder-builders entrepreneurs, and the US has one of the friendliest places for entrepreneurs on the planet (for now).

Taking a more social perspective, though, reveals that this mindset is one of the reasons behind the rise of identity politics, in fact. We have a generation of people who believe, with all their heart, that the generations that went before them were raised exactly like them: no one earned anything, everything was given to them, everything was immediate – and all of it was based upon how privileged you were.

After all, why not? What exposure to other methods do they have, collectively?

Like Diogenes, I was not among my peers in terms of motivation, ambition, or drive. I was of the “slacker” generation (though not “part of” it), and, like Diogenes, needed to cope with the accusations cast upon my entire generation.

Like Diogenes, I was not among my peers in terms of motivation, ambition, or drive. I was of the “slacker” generation (though not “part of” it), and, like Diogenes, needed to cope with the accusations cast upon my entire generation.

The key difference here is that while those in the Gen-X generation were told “you can have everything you want,” it was always with the caveat that “if you are prepared to work for it.” Even popular movies (like Dazed and Confused, Singles, Clerks, and Reality Bites) about Gen-X made the case that life was not going to hand you something for nothing. Those protagonists rejected the idea of hard work, sacrificing future gains for immediate gratification, but they did it knowingly.

In other words, to put it into Sinek terms, Gen-X had a clue as to how to climb the mountain, but they chose not to. Millennials don’t have a clue how to climb the mountain, so they believe that anyone who got to the summit was dropped there by helicopter.

What Sinek Gets Wrong

I included the breakdown above, not only for those who can’t be bothered to watch the video, but also because it’s important to understand how Sinek lays out his entire argument.

While the 90% of Sinek’s talk – the sources of the issues and the nature of the problem – are spot on, his remaining 10% conclusion is, unfortunately, compounding the problem.

Sinek proposes one more target to point a finger to – corporations and workplaces – to excuse responsibility from Millennials. He explicitly states that corporations are not helping Millennials overcome the challenges that should have been taught them by their parents and schools. He does not, however, identify why.

I think he knows that if he were to address the why, he would face the criticism that it is neither the responsibility of corporations, nor their charter, to continue to “help them overcome.” Now, I don’t think that he believes he is espousing corporations take on the parenting-by-proxy (at least, I hope not), but that is effectively what he is doing. It is unreasonable to accuse corporations of a “lack of leadership” for failing to accomplish something that isn’t their purpose or, even, in their best interest, to begin with.

Why isn’t it in their best interest?

Because his conclusion not only doesn’t solve the problem, it never addresses it in the first place. He has spent the bulk of his talk on why Millennials are not receptive to the very solution he proposes. If we grant him his premises – that Millennials do not know how to cope with stress, they do not have the patience to learn the scaffolding process to success, they demand instant gratification or they will quit – then how are corporations supposed to succeed given what they have to work with?

If, as he points out in his talk, there is a class of people who quit because they aren’t making an impact in 8 months, why would anyone spend the time, energy, money, and effort, to invest as if it was proper to assume that wasn’t going to happen? More to the point, why would that be corporations’ fault? Remember, Sinek identifies this behavior as an addiction on the part of Millenials. He makes no attempt to reconcile the fact that corporations are supposed to somehow, magically, fix their addiction as well as make them productive employees with “impact.”

Sinek spends several minutes of explaining that Millennials have been asked, throughout the course of their life, what it is that they want and even they can’t explain it properly. More to the point, Sinek explicitly states that there is an attention-span problem, as any efforts to get Millenials to focus on the task or relationships at hand are trumped by the addiction issues, then it does not matter if it’s parents, society, or corporate leadership that attempts to solve the problem if Millennials themselves don’t acknowledge their role in how they got there, or how they have a role in fixing the problem.

Sinek’s sin, then, is one of omission as well as substitution. He omits the need for Millenials to take responsibility for learning coping mechanisms that go against the grain of everything they’ve been taught. They were sold a bill of goods, yes, and it wasn’t fair (definitely), but complaining is not a course of action, and it’s not a solution.

The problem is that for many Millennials, complaining is the solution. They have learned – repeatedly – that complaining about something will force someone else, someone in authority, to act. Someone said something mean to you? They must be punished. Someone said something that makes you feel uncomfortable? They must be fired. Someone used a wrong pronoun? It’s genocide. It’s up to the parents, the corporate management, or the government to actually do something about it. Hey, I’ve complained about it, my job here is done.

What Is The Best Course of Action?

Someone else’s problem

Simply transferring the onus of responsibility from one proxy to another doesn’t actually solve the problem. If what Sinek says is true, and Millenials have no built-in coping mechanism, they must learn how to have one. Simply finding a new group to blame only kicks the can down the road for someone else to deal with.

Even supposing that Sinek is correct, that Millennials are victims of someone else’s good intentions, it does not change the situation for them. The people who are in this situation (yes, “not all Millennials, etc.”) need the ability to finally learn the coping mechanisms that are missing.

That means, then, that they need to understand that it’s okay to make mistakes. Not just for them, but for others as well. It’s okay to fail. It’s okay to come in last and learn from the experience, find motivation. The reason why the participation ribbons fail so badly is that it teaches the lesson that no matter how hard you try, the effort is meaningless.

Think about it – if what is important to this generation, what is so addictive, is the validation of self, then participation ribbons are the worst thing to do. Why would anyone make an effort to overcome any obstacle at all, improve, if there was no recognition in it?

We can argue all day long whether or not the motivation is useful or not, but that is not the point. The fact that such motivation is the constant ping of satisfaction from a “like” or a new friend request or a new follow, and as a result pretending that it doesn’t exist – especially now that it’s been baked into a generation – is futile.

We can argue all day long whether or not the motivation is useful or not, but that is not the point. The fact that such motivation is the constant ping of satisfaction from a “like” or a new friend request or a new follow, and as a result pretending that it doesn’t exist – especially now that it’s been baked into a generation – is futile.

One only needs to take a look at the public shaming to see the nature of the problem. We have moved from a mindset of “I disagree with you” to “you are an evil person” in the blink of an eye. With no sense of perspective, monolithic value judgments are de rigeur. It’s not, “I disagree with you;” it’s “you’re a racist!” It’s not, “Men and women have differences;” it’s “you’re a sexist!” It’s not, “Freedom of Speech is important;” it’s “You’re a Nazi!” “You’re a Fascist!”

God help anyone who fears they might be “wrong” in the eyes of the world. Is it any wonder that the self-esteem of this generation is the lowest in decades, as Sinek states? How horrible it is to not even know if you’re wrong, but be afraid to find out, “just in case?”

Final Thoughts

It is understandable that Millennials would react to Sinek’s analysis – and this one – with some negativity. After all, it’s what Gen Xers did when we suffered the same accusations:

I remember feeling the same way when I graduated college in 1991. It may be difficult to remember for some, and unknown to others, but Wicked Jester’s grievance about the “mess of the economy we were left with” was precisely the complaint Gen Xers had during that early recession.

It’s all a matter of perspective, however, which is the actual point. 2017 marked the the best growth in the previous 3 years. And yet, the perception is that all we are “left with” is the ability to complain. Complaining without a course of action, however, is precisely why Millennials find themselves on the business end of this criticism, and it’s going to take more than someone else to solve their problem for them. Again.

Comments

This is the challenge for leadership to reach and motivate the largest segment of our workforce – the CNAs, and evening/weekend dietary departments.