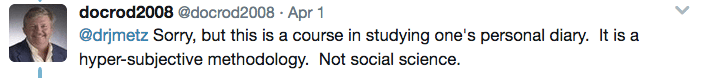

Recently I was tagged in a Tweet about a professor teaching a course on Autoethnographies. Anyone who knows me knows just how much I absolutely loathe the damn things, because the term is simply a fancy way of saying “I want to get academic credit for my diary entries.”

See what I mean? Part of the problem is the absolute hyperbole that surrounds them, as evidenced by the professor’s own subsequent tweets.

Their destruction, huh? Wow. That’s some pretty heady stuff there. This could be a catastrophe of epic proportions!

Our peril! Holy crap! Break out the Microsoft Word before it’s too late!

[youtube=”https://youtu.be/cMVhctL_uic”]

Why do I hate it so much? Because academic professors are teaching undergraduates and graduate students that this is legitimate scientific research:

As I’ll point out in a second, “autoethnography” is the exact opposite of “good research.” This is not research. This is public emotional masturbation and deserves the exact same reaction as the non metaphorical kind: disgust.

Backing Up: What is Ethnography?

It might be useful to understand what an Ethnography is before we start really tearing into an autoethnography.

Ethnography is a study of culture. At the risk of paraphrasing too much, it’s a process by which researchers attempt to understand a complex interaction of a series of people that constitute a characteristic all its own. It identifies the norms and behaviors, values and characteristics that make a culture what it is, and not some other culture.

Ethnography is a study of culture. At the risk of paraphrasing too much, it’s a process by which researchers attempt to understand a complex interaction of a series of people that constitute a characteristic all its own. It identifies the norms and behaviors, values and characteristics that make a culture what it is, and not some other culture.

It’s a time-consuming and complex process, because the researcher becomes the agent of understanding. Ethnographers go to great lengths to remove themselves from the subjects of research because they do not want to contaminate the findings. They spend a great deal of time sussing out their biases. Those who have gotten into trouble have done so because they couldn’t remove themselves enough.

This is done specifically because examinations of culture that are about the researcher are useless. It tells us far more about the person than the group, and as a result any examination effort that explains more about the research tool than the research subject can only be interpreted as a failure.

This is done specifically because examinations of culture that are about the researcher are useless. It tells us far more about the person than the group, and as a result any examination effort that explains more about the research tool than the research subject can only be interpreted as a failure.

The idea of good research is that an ethnography can help expand an understanding of a group of people that is independently verifiable. That is, if the method is done properly, another researcher using the same methods should be able to, independently, come up with the same conclusions.

What the Hell is Autoethnography?

In a nutshell, the term autoethnography is made up. It’s the Astrology of academic inquiry, the Homeopathy of epistemology.

The earliest book on the subject I can find comes from the late 90s, entitled Auto/Ethnography: Rewriting the Self and the Social (Explorations in Anthropology) by Deborah Reed-Danahay. Here is how Amazon describes the purpose of the book:

In departing from the traditional stance taken by anthropologists, who study ‘others’ ethnographically, this timely book explores forms of self-inscription on the part of both the ethnographer and those ‘others’ who are studied. Informed by developments in postmodernism, postcolonialism, and feminism, this is an original contribution to the growing dialogue across disciplinary boundaries. The chapters build upon recent reconsiderations of the uses and meaning of personal narrative to examine the ways in which selves and social forms are culturally constituted through biographical genres. Ethnic autobiography, self-reflexivity in ethnography, and native ethnography raise provocative questions about a range of issues for the contemporary scholar: authenticity of voice; ethnographic authority; and the degree to which autoethnography constitutes resistance to hegemonic bodies of discourse. Examined here in a variety of cultural and political contexts, writing about the self offers challenging insights into the construction and transformation of identities and cultural meanings.

Now that you’ve glossed over that quote without really reading it, I challenge you to read it once again. This time, look at all the “believe in yourself” justification for the process: “Self-reflexivity,” “authenticity of voice.”

Not to mention, the self-aggrandizement of the “method:”

- “Departing from the traditional stance” (translation: doing things that need to be valid and verified is too hard, so we need to dismiss them first)

- “Resistance to hegemonic bodies of discourse” (translation: the called us out on our crap and wouldn’t publish us)

- “Informed by developments in postmodernism, poscolonialism, and feminism” (translation: every means that people go out of their way to complain about the world around them)

- “Raise provocative questions about a range of issues” (translation: we’re going to make as much stuff up as possible and accuse people of being racist, sexist, homophobic, or any other name we can think of for challenging us)

Am I going too far? I don’t think so. Remember, making something complex out of the simple is the characteristic of a weak idea.

[youtube=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjNJX64cBOE&utm_source=email&utm_medium=email”]

You should note that the focus on self – and then couching it in terms of culture – is a contradiction in terms. This is like saying that “I’m a married bachelor” and, quite frankly, incorrect by definition.

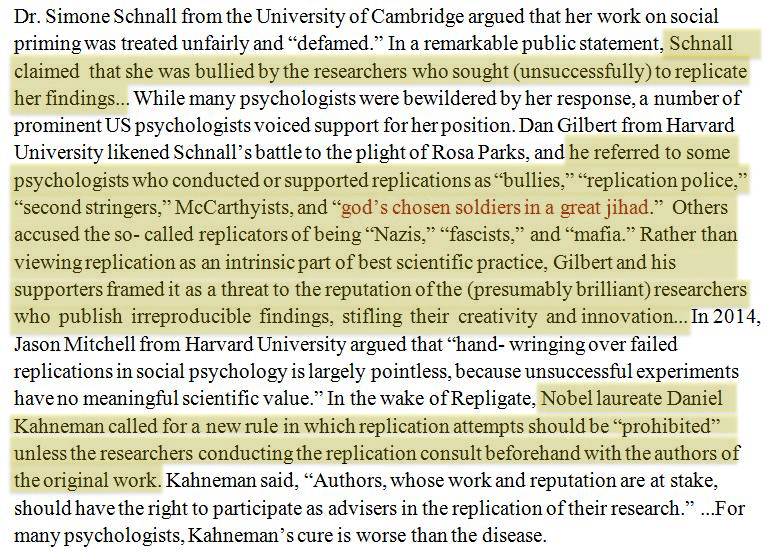

This approach (I can’t even bring myself to call it a ‘method’) doesn’t just eschew external validation, it actively attempts to crush it:

Don’t replicate me, Bro!

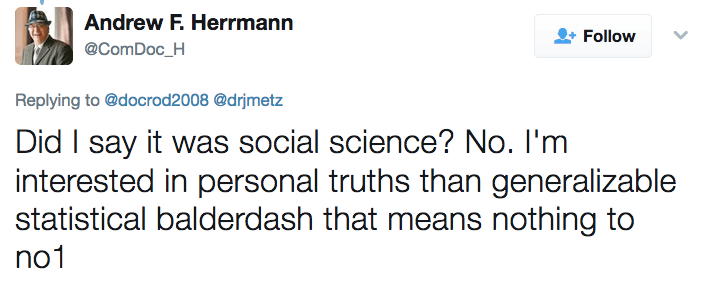

And yet, this deplorable attitude is being taught to undergraduate and graduate students as not only legitimate, but all other validated forms of inquiry are “balderdash:”

Dr. Herrmann claims to be more interested in “personal truths.” Given the fabricated nature of autoethnography, is it any wonder that he’s interested in a fabricated “truth” as well?

There Are No Such Thing As Personal Truths

Why do I say there’s no such thing as “personal truths?” I couldn’t say it any better than David. K Johnson in The Big Questions of Philosophy:

The notion that something can be true for one person but not for another, reflects an idea called individual relativism. Now, of course, it can be true that one person believes something and another does not. And sometimes “X is true for me” is just kind of a lazy shorthand way to say “I believe X.”

But the fact that someone believes something, does not make it True. I can believe that you don’t exist, but that doesn’t make it True. Generally stated, a belief is true if it matches up to the way the world is. And if two people disagree about something, it can’t be that both people’s beliefs match up to the way that the world is. So, what each believes can’t be true ‘for them.’

If there were such a thing as an “auto” ethnography, how would one be able to separate out him/herself to know if their biases are properly controlled? How could we know if they aren’t simply delusional (and, let’s face it, we’ve seen a lot of delusional college students in the past couple of years – the very ones likely to take this course, in fact)? Remember, we are simply supposed to accept whatever conclusions and findings they have without question.

There really is no way to go through this exercise and come out the other side “knowing” anything new and useful. Any program of study must be rooted in some method of knowing if your conclusions are even close to being accurate. Autoethnographies fail because their premise is Sum Ergo Veritas: I am, therefore Truth.

The fatal flaw of autoethnographies: Sum Ergo Veritas: I am, therefore Truth

Sure, any person can find insights through introspection, but there are well-understood intrapersonal and psychological methods for doing that.

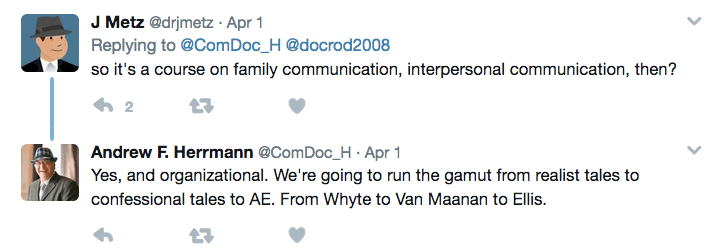

So Dr. Herrmann agrees that it’s a course on different types of communication, but completely rejects communication theory, philosophy, and psychology as “balderdash.” If his stated goals are his actual goals, why is he not teaching how to do phenomenology? Or epistemology? Hell, students could take the Philosophy course by David K. Johnson (from where I got the quote I mentioned above) and learn more through pondering the questions of How We Come to Know Truth than by wasting time with autoethnographies.

Wasting time? I’ve got a Autoethnographic Wall of Shame for your perusal at the conclusion of this blog.

In any case, note that the course (as described) simply assumes that enlightenment will come through the writing process.

In any academic inquiry you must be willing to accept that you are wrong. We’re not talking about whether or not taking a “post-colonialist” or “feminist” look at yourself will tell you that you’re wrong – in light of those lenses you’re always wrong – it has to do with determining whether or not you can rely on your premises, your conclusions, or the process that got you there. There exercise here, though, is self-referential – the act of doing an autoethnography is automatically true. As if the process itself was some magic bullet for ultimate enlightenment.

I asked a final question, to which I received no answer, but I think upon reflection that I know it after all.

As I mentioned before in another post, the purpose of social justice is to focus on metacommunication. This is a course in doing just that. The actual content of whatever they write about does not matter (the communication). It’s the act of writing about whatever the content is (the metacommunication) that is key – and of course they will find all kinds of “problematic narratives” to correct.

It’s the intellectual equivalent of bleeding the patient to improve their mental health:

You’ll feel so much better when we’re done!

The Curse of Perfection

Much of the academic discourse in the past decade has begun to heavily stress this notion of “personal truths,” and is a natural outgrowth of the pandering to the 90s-born Participation Ribbon Generation. Growing up sheltered, believing that they were perfect without effort, without being tested and challenged to grow through adversity, Academia is now codifying this narcissism as legitimate research methodology.

Thing about it: perfect kids grow up to be told that they are perfect without needing to even try. They enter college with the attitude that they have everything right, and everything that went before is wrong. How do they know this? Welcome to the Social Justice Tautology: It’s racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, etc. – because they say so.

Colleges and Universities kowtow to their demands, fire their presidents and chancellors, allow them to assault their professors and humiliate them in public without so much as a “hey!” Do a quick online search for “students demand” and be prepared to wonder if you’ve stumbled onto a series of articles from The Onion.

As if that isn’t bad enough, these same universities and colleges pay hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to “Diversity Officers” who establish ideological purity tests for faculty and staff to adhere to, lest some of the students be “triggered” or feel “harassed” by the use of a wrong pronoun. Governments have gotten into the act to elevate the thought police to the level of hate crimes (see e.g., Canada’s C-16 bill).

Teaching “autoethnography” is, in my opinion, simply cruel. It couches everything in ‘problematic’ terms, and implores students to find “truth” by beating themselves up with a “post-modernist, post-colonialist, feminist” lens.

There is no actual opportunity to learn from one’s mistakes. To make a mistake is to be labeled. To be labeled is to be a bad person. And to the social justice warrior, to be a bad person is to fall from grace. You were once perfect with perfect morality – to change your mind is to move away from perfection.

Stop The Madness

If legit Social Scientists who actually understand how to do proper research methods don’t speak up – and do it soon and loudly – your precious discipline will disappear in a legacy of temper-tantrums and caterwauling. Your Ph.Ds – and mine – will never be seen as legitimate, no matter how thorough and rigorous your process was.

Balderdash, indeed.

I’ll close this with examples of autoethnographies that are supposed to be taken as some sort of revelatory epiphany worthy of academic consideration. Remember, they gave people Ph.Ds for some of this crap.

Think of it as the “insane drivers dash cam compilation” of modern academia.

(H/T @RealPeerReview)

This is an actual PhD dissertation examining the author’s experiences wearing their grandmother’s kimono… https://t.co/Kh2aJtygbC pic.twitter.com/mEFro3nui6

— Amir Sariaslan (@AmirSariaslan) April 13, 2017

Researcher wrote a peer-reviewed paper about how they dealt with their father’s passing. https://t.co/mWjLoS7Uuc pic.twitter.com/YLLhJEv0od

— Amir Sariaslan (@AmirSariaslan) April 4, 2017

An autoethnography on asian/black gay relationships https://t.co/O8NmSXZ98b pic.twitter.com/7UxAgnyciJ

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) April 4, 2017

Autoethnography about knitting:https://t.co/YN0J20TETp pic.twitter.com/67H3OrLbah

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) April 3, 2017

International Review of Qualitative Research

4 researchers write about sharing a pink-wheeled bike at campushttps://t.co/LokDJvpprL#NoJoke pic.twitter.com/dFytgifkL2— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) March 31, 2017

Doctoral thesis about walking around and experiencing architecture. https://t.co/11phBYiKUW pic.twitter.com/IUvo1UR8ED

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) March 29, 2017

A feminist critical examination of walking around and listening to streamed music.https://t.co/dniAjNJTJh pic.twitter.com/Mhga7cxSDn

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) October 12, 2016

Academic writes a peer-reviewed autoethnography on not being able to sleep after Trump won the election https://t.co/sAJ8FLzKzd pic.twitter.com/MiSfDJTVVi

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) March 16, 2017

A pharologist is so depressed that nobody cares about her field she writes an anxious autoethnography about it https://t.co/V75qwCPCc9 pic.twitter.com/31g37WFRib

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) March 15, 2017

Thankfully, this is academia and not a therapy session. Wait, what? https://t.co/n7UWXeLRP3 pic.twitter.com/nG2k1Z3Avn

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) March 1, 2017

#RetroNRPR: auto(erotic)ethnography – “television as lover” https://t.co/IX8VJevb0b pic.twitter.com/nJCAxZchBL

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 25, 2017

An ethnographic study on gay resorts highlights the absurdity of ‘non-biased’ and ‘value-neutral’ results https://t.co/cxzab9P9gj pic.twitter.com/v3J3BvH5AN

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 27, 2017

Ethnographer publishes paper on how to “resist” institutional review boards (IRBs). Making up ethical shit is hard. https://t.co/sfnOpsXQAj pic.twitter.com/4F0xNIjNIY

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 24, 2017

What would the world have done without this great piece of scholarship on being a “Rude Boy”? https://t.co/qY4xsVrYDE pic.twitter.com/SSyVrIlu8K

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 24, 2017

Just when you thought that autoethnographies couldn’t get any more interesting. https://t.co/tbuDYnLyU6 pic.twitter.com/1vLNdq6cGM

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 20, 2017

That awkward moment when a duoethnography turns into an autoethnography. https://t.co/IXz4eS1z1i pic.twitter.com/1UJ8a94PEq

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) January 2, 2017

Groundbreaking findings in ethnography: You feel warm and sweaty while exercising https://t.co/K7i28XZtau pic.twitter.com/hSPotxEqzy

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 17, 2017

Someone mentioned gardening. We found an autoethnography for that too. https://t.co/bL0c0hCnjL pic.twitter.com/bQonm6uMtm

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 20, 2017

Autoethnography of a scholar’s child going to school. A horrific account of ‘learning discourses’ and neoliberalism https://t.co/kY5DlcwPKc pic.twitter.com/ciIqfD8Cci

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 23, 2017

“Confessions of a Video Vixen: My Autocritography of Sexuality, Desire, and Memory” https://t.co/qmLoRfgOtr pic.twitter.com/JwX4FduwMg

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 18, 2017

This researcher is so awesome that her stories are generalizable to all Latinas. https://t.co/s8XL5JI0kR pic.twitter.com/dOCgmvieOA

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 18, 2017

This does not seem creepy at all. https://t.co/uSZGORenpZ pic.twitter.com/boenM0YOgr

— New Real Peer Review (@RealPeerReview) February 19, 2017

Comments

Pingback: Transcript: 2027 Ph.D Graduation Commencement Speech – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: Understanding Metacommunication – J Metz's Blog

The “auto-ethnography” is the source of our cultural demise. A subjective presentation of a personal perspective. No wonder 80% of papers coming out of the Humanities will never be cited. The PhD is still considered the gold-standard, yet no one outside of the academy knows what useless piece of shit it is. Every single PhD built on a so-called “auto-ethnography” needs a big fat ASTERISK on it so that we may begin to separate the wheat from the chaff.