When I was in graduate school and forced to read all about Communication Theory, I was caught in a deluge of various ideas from Philosophy, Psychology, Sociology, Political Science, and even Law, Mathematics, Biology and Physics.

When I was in graduate school and forced to read all about Communication Theory, I was caught in a deluge of various ideas from Philosophy, Psychology, Sociology, Political Science, and even Law, Mathematics, Biology and Physics.

One of the things that got reinforced over and over was something that I learned my very first day of college when I was 18 years old:

Everything is related to everything else.

In the dozens (hundreds) of books, chapters, articles, and studies that I’ve read, it was easy to miss the importance of ideas conveyed within. Now I realized that what seemed like a throw-away line at the time turned out to be a major, pivotal concept for human understanding, and at the time I missed it.

It’s the concept of Metacommunication.

This is a long-form essay, so I hope that you will bear with me. I can guarantee you (or your money back!) that when you are finished with this article you will see the nature of your relationships more clearly, where “communication breakdown” occurs, and how you can improve your interaction with people that you love as well as those you don’t like very much. Most importantly, you will understand how to disagree with someone in a productive manner.

This is a long-form essay, so I hope that you will bear with me. I can guarantee you (or your money back!) that when you are finished with this article you will see the nature of your relationships more clearly, where “communication breakdown” occurs, and how you can improve your interaction with people that you love as well as those you don’t like very much. Most importantly, you will understand how to disagree with someone in a productive manner.

What is Metacommunication?

In actuality, there are really three concepts that are closely related to one another:

- Communication

- Metacommunication

- Meta-metacommunication

Part of it, I think, was the fact that people get very confused about which is which (and for very good reason), and because of that, I don’t think many people actually care to learn about how nearly 100% of all misunderstandings (not to mention much of the strife and conflict occurring in politics today surrounding “freedom of speech”) stem from this very fundamental tenet of human relationships.

Definitions of terms that include the term in the definition are, usually, useless. So, let’s try to break it down in simple terms (at the risk of being imprecise, but it should all become clear soon enough).

Definitions of terms that include the term in the definition are, usually, useless. So, let’s try to break it down in simple terms (at the risk of being imprecise, but it should all become clear soon enough).

For the sake of such simplicity, then, let’s define (operationalize) the word “communication” to mean when you are conveying information. Another way to think of it is that communication = a particular message. It’s a broad definition on purpose – this can be:

- A conversation between two people (one-to-one communication)

- A speech (one-to-many communication)

- Non-fiction (like describing the weather)

- Fictional (like a book, movie or a TV show)

- An original YouTube video (more on this in a second)

Because I don’t want to “call out” anyone here, I’ll put my own work under the microscope. The articles I write on storage, for instance, those would qualify as an act of communication (conveying information). Note that this does not mean that other pieces of work can’t be referenced or sourced, but for our purposes here we’re really referring to something that “stands alone” (again, trying to keep things simple for explanatory reasons).

Now, if we want to talk about, respond, or react to a piece of information, message, or content of communication, there is a special word for it: Metacommunication.

Meta-communication can be defined as “talking about communication.”

What does this mean? Essentially, it means that you are one step removed from the initial act of communication.

When I write reviews, for example, I am not participating in the initial act of communication, but rather talking about that act of communication. An example might be my review of various video games, or my breakdown of the debate between Kristi Winters and Sargon of Akkad. Effectively, it’s as simple as examining a piece of content and communicating about it.

Reviews and commentaries are only one example of metacommunication, but they are not the only examples. When a couple goes to therapy, for example, and recounts an argument they may have had in the past, they are talking about their communication. When a news organization spends hours deliberating one of Donald Trump’s tweets, they are engaged in a metacommunicative exercise.

This is, unfortunately, where things begin to get messy, as we’ll soon see. Before we allow that to happen, let’s try and keep things simple for just a little bit longer.

Meta-metacommunication is, as you may have guessed, “talking about ‘talking about communication.’”

Meta-metacommunication is, as you may have guessed, “talking about ‘talking about communication.’”

Often times we use meta-metacommunication without ever realizing it. Correction: almost all the time! But here are some examples of what meta-metacommunication looks like:

- The aggregated review scores of movie critics on sites like Rotten Tomatoes

- The New York Times Bestseller List

- Determining whether or not Roger Ebert’s movie reviews were good or bad

- Remember the debate review I wrote about above? Well, when a forum starts talking about my reviews of the debate and I need to talk about their metacommunication, which is meta-metaccommunication!

There are more – much more – which we will get to below.

Where things get messed up

So far, nothing we’ve talked about is really controversial. Everything seems pretty straight-forward, doesn’t it?

Things get really screwed up, though, when you start to realize that not only do people confuse metacommunication for communication – always – but that the acts of communication themselves can float between different modes. That is, acts of metacommunication can be treated as communication. As I’ve written elsewhere, it is not uncommon – especially in recent political discourse – to treat metacommunication as the communication, and ignore the initial act of conversation altogether.

Metacommunication is very important. When a message is determined to be false (e.g., a lie), that is a metacommunicative evaluation. A false message can not self-declare; this is how Captain Kirk tripped up the robot in the original Star Trek – Kirk beat the robot with a logical inconsistency. A self-referential metacommunicative statement is, by definition, illogical.

[youtube=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFy4zQlWECc”]

Of course, you knew that, right? You already knew that the reason why the robot couldn’t survive an illogical statement was because Kirk was conflating communication with metacommunication, right? I confess I didn’t realize this until I began to understand the importance of the differences between these different communication modes. Hey, I’m a bit slow on the uptake sometimes.

Separating What We’re Talking About

Above, I put in “YouTube” videos as acts of communication. That would make “reaction videos,” then, metacommunication. Reaction videos to reaction videos, of course, would be meta-metacommunication.

Let’s change tack for just a second, before coming back to our main point. In technology, we are often concerned with metadata (data about the data), and it follows the same principle. Any piece of data is like a can of food with no label on it. The label doesn’t contain the food, but it contains the information about the food. Lose the label, and you lose significant information about what’s inside the can.

Let’s change tack for just a second, before coming back to our main point. In technology, we are often concerned with metadata (data about the data), and it follows the same principle. Any piece of data is like a can of food with no label on it. The label doesn’t contain the food, but it contains the information about the food. Lose the label, and you lose significant information about what’s inside the can.

A message is a lot like the food in the can. People can talk about the can of food without actually eating (experiencing) the food inside. In communication terms, then, people can talk about a communication message without actually experiencing the message itself.

In a lot of ways, focusing on metacommunication is a lot easier than dealing with the messages themselves. It’s a lot easier to focus on the pretty picture on the label than actually try out the food inside. In fact, if you were to solely look at what substitutes for discourse in today’s social media, you will see that people are very comfortable relying solely on metacommunication for their intellectual nutrition.

To them, it’s important to know who is saying a particular message in order to know whether to listen to the message in the first place. This is, of course, admirable up to a point. After all, you may want to know if the label-less tin can in front of you contains chili or dog food, right?

But to many people, the metacommunication isn’t enough. They want to know the meta-metacommunication first. That is, they want to know what other people think of the person who delivered the message before giving the message its due.

But to many people, the metacommunication isn’t enough. They want to know the meta-metacommunication first. That is, they want to know what other people think of the person who delivered the message before giving the message its due.

A recent example comes to mind. I was in a conversation with two friends, when one of them wanted to show a YouTube video that he liked. He didn’t explain anything about it, just that it was interesting. Curious, I awaited the beginning of the video to begin, but our third friend demanded to know who the speaker was so that he could do some research as to whether or not the people he already agreed with had approved or condemned the speaker, regardless of the message contained therein.

(Taking my own medicine here: the metacommunication is the communication in this example, which is why the content of the video is actually irrelevant to the point of the story. See what I mean when I say it can get messy?)

Living in a Metacommunicative World

There are no shortage of examples of how people are swapping these different modes in today’s political discourse, whether one-on-one or as groups. There seems to be a “breeding out” of the understanding, intuitive or not, of the differences between communication, metacommunication, and meta-metacommunication. This is bad. Very, very bad.

When people spend too much time in the metacommunication and meta-metacommunication, examples like the conversation between myself and my two friends above are the least of our worries. All of the discussion over “hate speech” and “free speech” and “speech as violence” exemplify how things can go terribly wrong.

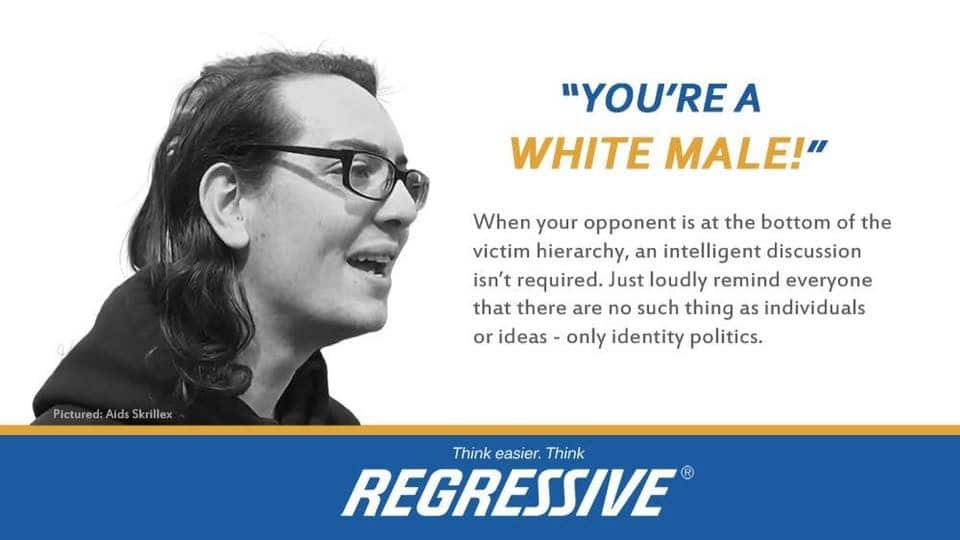

The real problem is when people substitute metacommunication for the actual content. In this case, you see the effects immediately. Remember the statement above: “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.” Now, let’s take a different metacommunicative approach: “It’s not what you say, it’s who says it.”

This is why so many hateful, racist, sexist, and horrific behaviors can be committed and absolved by well-meaning people. They excuse the message because they approve of the speaker. Alternately, the condemn the message (without understanding the message) because they disapprove of the speaker They have accepted that the metacommunication is far more important than the message that is being conveyed.

How does this happen? Well, if you have people who float between meta-communication and meta-metacommunication on a moment’s notice, every conversation becomes like Captain Kirk’s. You get people shouted down because of their metacommunicative status.

Think about it this way: “hate speech” looks like a metacommunicative evaluation. However, in reality, it is a meta-metacommunicative conclusion.

Here’s what I mean.

Let’s say that you have a message that says, “Purple people don’t drive cars.” (Since there are no such thing as purple people, I think I’m on safe ground here using an example that they don’t drive cars, since non-existent people can’t drive cars).

The statement itself is innocuous. That is, among the metacommunicative characteristics (the tin can labels) you can apply, there is no valuation of the statement. In order to interpret a value judgment (i.e., to reach a conclusion that the statement qualifies as “hate speech”), one must add in an “extra layer” of analysis.

The statement itself is innocuous. That is, among the metacommunicative characteristics (the tin can labels) you can apply, there is no valuation of the statement. In order to interpret a value judgment (i.e., to reach a conclusion that the statement qualifies as “hate speech”), one must add in an “extra layer” of analysis.

To do this – to turn this episode into an example of “hate speech” – we must identify what is mentioned in the message, and then make an interpretation based upon that. In this case, we identify the components of the message (“purple people”, “don’t,” “drive,” & “cars”) and then must choose to determine what’s important. In this case, the key terms we would need are “purple people” and “don’t.”

Just when you think you had it…

By this point, the actual meaning of the sentence is lost. We have identified that “purple people” have been mentioned, and they “don’t” do anything. The new message is that “purple people” are associated with “don’t” (otherwise known as accused of, in modern discourse) and in this way it is very easy to initiate a value judgment based upon the new message.

In this way, then, we have managed to shift the focus from the original communication to the meta-communication, where it’s easy to attack. In technical terms, the meta-metacommunicative message is that the metacommunication is “hate speech”, not the original message.

Where Emotions Run High

I once had a pivotal meeting with my advisor as I was working through my dissertation, and he said something that has stuck with me ever since. It’s only now, though, that I can place it into a context that underscores how profound the thought really is.

He said that ultimately, at the end of the day, people want to know what is “good.” Because of this, it’s easy to work our way backwards and see that generally speaking, people want to be “good,” they want to be seen as good, and they gravitate towards “good.”

Being “Good” is all that’s important, even when you have to be Evil to be that way.

“Good,” however, is a metacommunicative concept. That is, you have to evaluate a message as “good” or “bad,” but when emotions really get out of control is when we are not sure if we’re discussing a message, or the metacommunication of a message (thus making the evaluation a meta-metacommuicative exercise).

Emotions begin to run high (very high) when we try to force-fit metacommunication in such a way that it can only be seen as “good.”

Unfortunately for those who value accuracy in language, or adherence to the truth in a message, it is very easy to weaponize metacommunication so that some messages are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ based upon the metacommunicative aspects of those messages, rather than the actual content itself.

Weaponized Metacommunication

There is no shortage of examples of where this is the case. I’ve written about this before, and that still holds very true, but now you may have a better understanding of the communication mechanics behind the effect.

There is no shortage of examples of where this is the case. I’ve written about this before, and that still holds very true, but now you may have a better understanding of the communication mechanics behind the effect.

This article is already too long, but here are some examples of how this shift from communication to metacommunication has been used to confused and obfuscate understanding:

Ad hominem (argument to the man) attacks. How often have we heard that someone is either instantly accused or immune from what they say based upon their metacommunicative characteristics? Or heard “check your privilege,” or “you are lost in your implicit biases” as a counter-point? These all are an appeal to metacommunication.

Permission to Speak. The act of identifying who is permitted to speak on a certain subject, or use certain words, is an example of an appeal to metacommunication. This is why so many conversations surround the use of the “n-word,” ‘c-word,” “t-word,” or any other “x-word” as being the exclusive perview of certain groups.

“Microaggressions.” This is a prime example how metacommunication is ripped away from the message (communication) in order to change the nature of discourse: “What you said is not what you mean.” Here’s a homework exercise. See if you can figure out how these researchers are playing with metacommunication and meta-metacommunication in order to create a tautological conclusion of what is “good” and “bad,” regardless of what the messages actually are.

Academic “Autoethnographies.” In modern academia, the trend towards autoethnographies exemplifies how the appeal to metaccommunication is intended to replace any message with the person making the message. This is also an appeal for immunity. Much like Kirk’s Dilemma, autoethnographies attempt to conflate communication with metacommunication in order to deflect criticism by shifting from one to the other.

Interpersonal Relationships. This one may catch many people off guard, but this is where the phrase ‘communication breakdown’ really happens. “You always do this,” or “I never said that” – these are all metacommunicative statements. When emotions run high (and you can look back upon your own disagreements in your own life) see how quickly people jump from communication to metacommunication to meta-metacommunication in a matter of seconds. The frustration that people feel often comes from trying to figure out “where they are” in the conversation. When two people refuse to stay focused on one mode or another, there is no possible way to come to agreement.

“You said this!” “No, I didn’t, you heard that!”

Academia. If you wish to look for some of the most profound (and disturbing), systematic abuses of the communication/metacommunication paradigm, you need look no further than academia. There is no shortage of examples of how entire disciplines are developed to ignore communication messages and focus solely on metacommunication.

There are many others, of course, but I leave that exercise up to the reader.

Consequences of Metacommunication qua Communication

Perhaps there is no greater threat to this process than the outright attack on freedom of speech. This, then, is the purpose for this article: to provide people with the arms and ammunition necessary to defend against the arguments against free speech.

At this point, you have all that you need to be able to see how the arguments against free speech depend on a focus of metacommunication (and meta-metacommunication). Whenever you have a conversation about this with someone, when they try to establish a case for why speech or communication should be suppressed, this is the foundation of the games they play to confuse you.

In the future, I may make a specific post about “Metacommunication and Freedom of Speech”, because it deserves its own, specific attention. I touched on it briefly above, but it certainly is far more complicated than a couple of sentences.

At this point, however, I hope that I’ve given you enough of a starting point to be able to understand how such a simple concept has radical, profound impact on the way that human beings interrelate.

Comments

Pingback: Weaponized Metacommunication – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: A Funny Thing Happened On The Way to the Forums – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: Thin-Skinned – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: Breaking Up With United – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: Examples in Metacommunication: Justin Trudeau – J Metz's Blog

Pingback: How To Achieve “Emotional Intelligence” – J Metz's Blog